Drawing Out the Text in Textile

Untitled. Silk, stainless steel, wool, crochet hook. 2016-17.

Looking up the word “text” in the dictionary, I see it that it comes from the Latin textus meaning structure or context as well as from texere, to weave. I have been revisiting this topic of text in text-tile (see blog post “Two in One Text-iles” for my last discussion of this) as I find myself occupied with plotting out lines of text in my synesthesia drawings and wondering yet again how I got from weaving to making drawings of writing. The answer is that weaving and writing are connected in the human brain as far back as anyone can trace. As Laird Scranton, a comparative cosmologist and software designer who has studied the living language of the ancient Dogon tribe of Mali, points out in his book, The Cosmological Origins of Myth and Symbol :

The Dogon priests refer to functional equivalences between certain civilizing acts…For example, there is a direct comparison made between the acts of weaving a cloth and plowing a field. Likewise, both the act of weaving a cloth and the act of cultivating a field are specifically equated with processes relating to the formation of a Word. The concept of the Word itself represents an act of speech which is closely associated with the processes that create life or that form matter. These are expressed in terms of the enigmatic notion that words are woven into the cloth, again both in relation to the formation of matter and in terms of human reproduction.

I am well familiar with the importance of weaving or creating cloth to human civilization but its connection to word-making and forming concepts and logical structures is hitting home for me now more than ever. For as I plot my words onto paper, I realize that I am still using the same elements to explore the same paradigm: applying pigment to fiber using a system of coded symbols to investigate light and my own questions of meaning. I have a growing sense that I am going in circles, trying to crack open the same mystery that has tantalized me for a lifetime. It’s as if my art work is strewn out behind me as I plod forward, trying yet another method for getting inside that light and indeed, myself.

I know at least that I am translating once again, like I did as a musician reading notes to make music and as a weaver reading drafts to make cloth. Here, I am using a system of my own synesthesia to turn written passages into visual compositions. An article in The Oxford Handbook of Synesthesia titled “Synesthesia and the Artistic Process” by Carol Steen and Greta Berman recently clued me into why I was drawn specifically to watercolor on paper for my current medium:

One problem for a synesthetic artist, then, is how to deal with the fact that their colors can be extraordinarily bright, the colors of light rather than pigments. For some synesthetes, their colors might be seen as similar to sunlight streaming through a stained glass window. For this reason, traditional techniques of oil painting cannot be satisfactory. The question is, how can one make a pigment look as bright as colored light? In order to achieve this, painters often work with pure, unmixed oil paint or watercolor taken directly from the tube…

But what, you might ask, are the written passages that I am encoding in these drawings? I know that people will want to know, but I am not sure yet how much of the plotted text I will make known in relation to each drawing. While some of the drawings are titled by what they plot (the names of the dead in the Memento Mori series for example), thus making the words obvious, most illustrate passages that are too long to title this way. They include my own poems, wishes or dream narratives as well as favorite writings from other authors. All have significant meaning for me and as such, comprise a sacred text. And isn’t there is a level of secrecy required to preserve the sacred? In the end, I see this hiding of the literal message, this coding, as a gift of privacy I give to myself, in service of preserving the mystery that is me. The medium is the message after all.

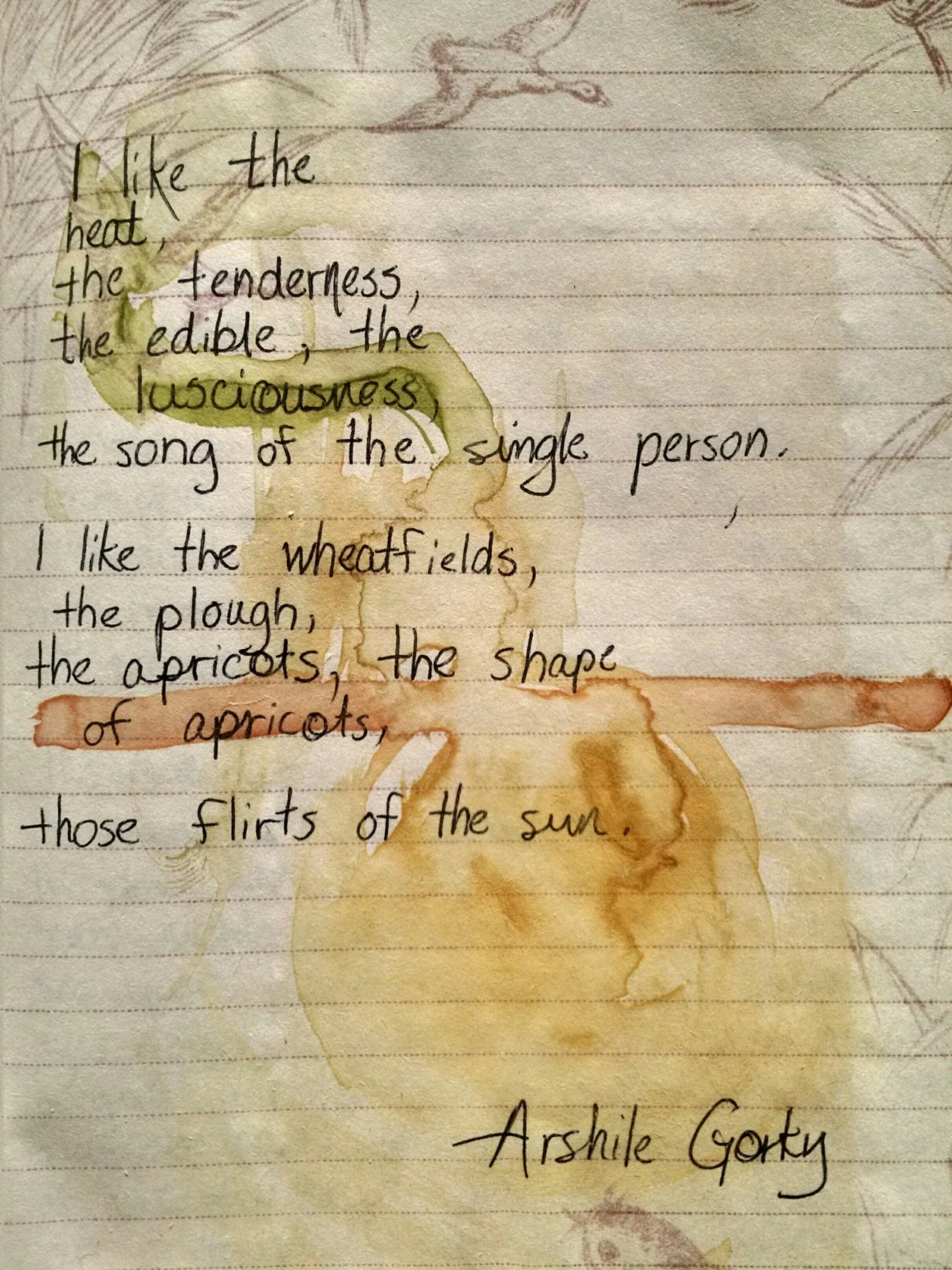

Illustrated journal text from the 1990s, early hint of my relationship between color and text